Shutting the door on pathogens causing bovine mastitis: The ‘Teat end’ status

Would you leave the main door of your house unlocked? No, of course not, as it works as a barrier to stop intruders from getting in. When it comes to preventing mastitis in dairy cows, the teat end also acts as a barrier that protects from pathogens causing bovine mastitis. In this post, we will help you evaluate the state of the primary protection against teat pathogens.

Preventing Bovine mastitis: Why checking teat status is so important?

The teat sphincter and teat canal are important primary barriers against pathogen invasion into the udder and prevent bovine mastitis.

Thus, it is essential that such structures should be in perfect physical and hygienic conditions to prevent intramammary infection (IMI) (M. de Pinho Manzi et al., 2011).

The “Teat Club International” suggested a range of teat condition scores for the evaluation of field data and divided them into short- (single milkings), medium- (few days or weeks), and long-term effects (several weeks) (NMC,2004).

a) Short-Term Changes In Teat Condition

Faults in milking machines or milking management are the primary cause of short-term changes in colour (pink, red or blue coloured), firmness, thickness or swelling of teats (no ring, garter mark or palpable ring), or degree of “openness” of the teat orifice (closed or open more than 2mm) (Mein et al., 2001).

b) Medium-Term Changes In Teat Condition

Machine-induced changes in the incidence of petechial haemorrhages or larger haemorrhaging may occur immediately or may take several days before becoming evident. Changes in teat skin condition associated with harsh weather or chemical irritation may take a few days or weeks.

When teats were intentionally irritated with a harsh chemical, the irritant effect was maximized after 1-3 days. Progressive healing from severe teat skin and teat-end damage can take 3-5 weeks. More typical degrees of irritation resolve in 10-14 days (Ohnstad et al., 2007).

c) Long -Term Changes In Teat Condition

The amount of hyperkeratosis varies dynamically, increasing from calving to peak lactation and then decreasing towards the end of lactation (Ohnstad et al., 2007).

It also increases progressively with parity (Shearn and Hillerton, 1995; Neijenhuis et al., 2002). Teat end hyperkeratosis is often influenced by seasonal weather conditions. The extent of hyperkeratosis and the degree to which it can be improved is related to teat shape being worse with long, slender or pointed teats.

There may, therefore, be a genetic influence (Ohnstad et al., 2007).

To simplify and streamline the procedure, teat condition should be evaluated immediately after the cluster is removed and before application of a teat disinfectant.

Mein et al., in 2001, looking at a scoring method developed by Neijenhuis et al. (1998), produced a simplified system for routine field evaluation giving a score to the teat end:

- No ring (N) a typical status for many teats soon after the start of lactation. This category includes teat-ends scored as 1.

- Smooth or Slightly rough ring (S) a raised ring with no roughness or only mild roughness and no keratin fronds. This category includes teats classified as 2.

- Rough (R) a raised roughened ring with isolated fronds of old keratin extending 1-3 mm from the orifice. This category indicates some breakdown in epithelial integrity. It includes teat-ends classed as 3.

- Very Rough (VR) a raised ring with rough fronds of old keratin extending >4 mm from the orifice. The rim of the ring is rough and cracked giving the teat-end a “flowered” appearance. This category includes teat-ends classified as 4 (Mein et al., 2001).

Teat ends with very rough rings with keratin extending more than 4 mm from the orifice (score 4) had the highest chance of developing IMI when compared to the other three categories. There is a clear relationship between intramammary infections and teat end status. (M. de Pinho Manzi et al., 2012).

Score teat condition on all teats of all cows in the herd if time and herd size allow. If time is limited and/or for large herds, score all teats of all cows in herds of up to 80 cows, or a random sample of at least 80 cows in herds with 80 – 400 cows, or at least 20% of cows in herds larger than 400 cows (Mein et al., 2001).

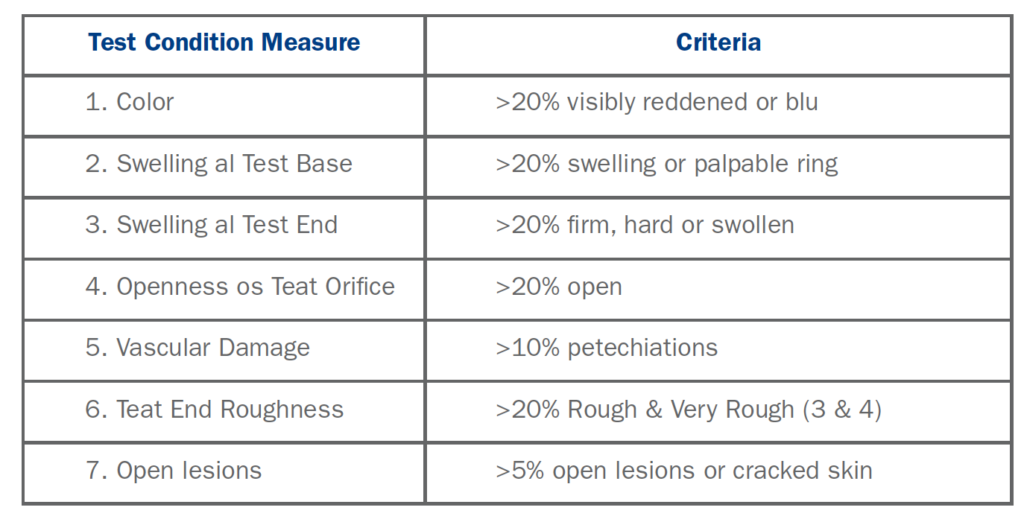

Table 2 summarizes all the relative criteria for evaluation of the results of teat scoring. The use of Table 2 can help with the evaluation and detection of a teat problem in a herd.

Content originally created for “the Mastipedia”.

Authors: Nicola Rota (Udder health and milk quality consultant).